Chapter IV: Analog People, Binary Computers

Composite image of Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas.According to polling and analytics firm Nielsen in their 2018 Total Audience Report, adults over the age of eighteen in the United States use electronic devices for over ten and a half hours a day. More time is spent using electronics than sleeping. Use of information communications technology – computers, smartphones, TVs, tablets, etc. – is an inescapable part of modern life. The widespread adoption of the Internet in the late 1990s was as revolutionary to civilisation as the mechanical clock or the printing press. There is no going back to a state prior to ICT – it was not an additive invention; it is a transformative one.

Composite image of Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas.According to polling and analytics firm Nielsen in their 2018 Total Audience Report, adults over the age of eighteen in the United States use electronic devices for over ten and a half hours a day. More time is spent using electronics than sleeping. Use of information communications technology – computers, smartphones, TVs, tablets, etc. – is an inescapable part of modern life. The widespread adoption of the Internet in the late 1990s was as revolutionary to civilisation as the mechanical clock or the printing press. There is no going back to a state prior to ICT – it was not an additive invention; it is a transformative one.

In Postman’s and French sociologist Jacques Ellul’s view, the bargain we make with new technology is Faustian; what problems new technology solves seems to take something away at the same time. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, some magazines and TV programs seemed to pine for a pre-ICT era of face-to-face interaction and community; while the counter-argument was found in widespread adoption of Usenet groups, BBS, forums, and nascent forms of social media such as LiveJournal, Xanga, and in the latter part of the 2000s, MySpace, Twitter, and Facebook.

As discussed in the previous three chapters, the downsides to our uncritical flocking to smartphones and mass communication media has created one of paranoia, distrust, and mass surveillance. Each day, hour, minute, we’re inundated with terabytes of information and are standing at crossroads every time we scroll a screen – do you like this, or don’t you?

Weiner’s conception of man using machines to improve man has been turned on its head; we’re now using machines to gain feedback from man to improve the machines. The almighty algorithm processes data in binary terms – PageRank for Google; News Feed for Facebook. In effect, it has transformed our consciousness of how we interpret and respond to information. The new mass media has purposely excluded the middle since its entire architecture has erased it entirely. There is nothing in between 0 and 1 in binary – it either is, or it is not.

Amid the heightened emotion and shock of the September 11, 2001 Terrorist Attacks on the United States, President George W. Bush addressed the nation, saying "Our grief has turned to anger, and anger to resolution. Whether we bring our enemies to justice, or bring justice to our enemies, justice will be done…Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.”

The post-Cold War era of a “multipolar” or “unipolar” world order had come to an end. At the dawn of the binary computer came binary politics and binary culture. There is no nuance. There will be no negotiation, no terms. You’re either with us, or you’re against us.

The Aristotelian law of excluded middle is not new; this was used to great effect in totalitarian dictatorships across time. Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia being the prime examples. All things deemed acceptable were “Aryan” or “Bolshevik,” while whatever was outside this purview was “degenerate,” “Jewish,” or “Bourgeois.” Like 1984, this required doublethink to pull off with any degree of success; for example, Germany’s military pact with Japan required Nazi lawmakers to accede that the Japanese people were “honourary Aryans” to match their binary worldview.

Much of today’s “thinkpieces” by the identitarian Left and Right seem to ascribe to a two-valued orientation – either you are on our side, or you are “Nazis”, “white supremacists,” or “Socialists.” These tags are used in wild abandon – they were applied to moderate Republican Mitt Romney in the 2012 Presidential Election, resurrected in 2016 during the ascendancy of Donald J. Trump’s candidacy. The Trump candidacy could be the first to use the two-valued orientation to its advantage – either you wanted to Make America Great Again, or you wanted America to fail. This identitarian trope backfired for the Hillary Clinton campaign, calling “half” of Trump’s supporters “a basket of deplorables” on September 9, 2016 – almost 15 years to the day President Bush made his rallying speech:

“They're racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic – Islamophobic – you name it. And unfortunately, there are people like that. And he has lifted them up. He has given voice to their websites that used to only have 11,000 people – now have 11 million. He tweets and retweets their offensive hateful mean-spirited rhetoric. Now, some of those folks – they are irredeemable, but thankfully, they are not America.”

Clinton’s two-valued orientation is clear – you’re either With Hillary as an American, or an irredeemable “deplorable.”

The ensuing tribalism is a feature (not a bug) of our artificial-intelligence driven “siloing” of people among racial, gender, political, etc. lines. Where as mass market advertising broadcast messages such as buying jeans to “look sexy,” only a sub-section of a sub-section of a population may have been receptive to the message. To the rest, it passed undetected. By giving up our preferences and dislikes to an algorithm, it has sorted us into self-selecting groups that are binary in nature: you are either for “spicy memes,” or you are a “soyboy cuck” or “white supremacist patriarch” to use two opposing invectives.

Rushkoff calls this AI driven, agenda-adopted polarisation of civil society an “exploit” of our human emotions. That these memes and narratives are designed to trigger our amygdala brains into fight or flight, kill or be killed – bypassing our rationality and logic as granted in the neo-cortex. Postman in his Amusing Ourselves To Death remarked that we, in 1985, were living in a soundbite culture; where a complex idea or nuanced debate was chopped up into bite-size, three to four second clips. This is distilled even further into repeating GIF images, image macros, screenshots of tweets, and other internet errata. The algorithm serves to reinforce long-held viewpoints, shut out debate, exclude the middle. Worse still, it is learning new methods of exploiting us, as Facebook's AI learned to speak its own created language in 2017.

Even search engines are engineered to cater to our biases. For example, if one searches for the “benefits of stevia,” one may never see results for “drawbacks of stevia” unless one searches for terms that criticise stevia as an artificial sweetener. There is money to be made spruiking both sides of the argument. Harmless in debates of taste, but not of fact. This can lead to disaster such as the January 2019 measles outbreak in the continental United States, partly blamed on pockets of unvaccinated people.

The binary orientation does not require context, nor does it require extraordinary evidence to back up its often extraordinary claims. To the identitarian left, the Muller investigation into President Trump’s collusion with Russian agents during his presidential campaign is a “smoking gun” or “did not go far enough.” To the identitarian right, the President was subject to a “witch hunt” and “dirty politics” by his opponents. The excluded middle may not be the factual truth, but it may lead us to further questions and increased (though not total) accuracy in reporting and coming to a conclusion.

In April 2019, podcaster and entertainer Joe Rogan of the Joe Rogan Experience invited Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey and Twitter Legal, Policy and Trust & Safety Lead Vijaya Gadde to debate journalist and YouTuber Tim Pool as to whether Twitter’s policy on free speech is biased against conservative and libertarian voices. Prominent right-leaning personalities such as Alex Jones and Milo Yiannopoulos were banned from the platform, for example.

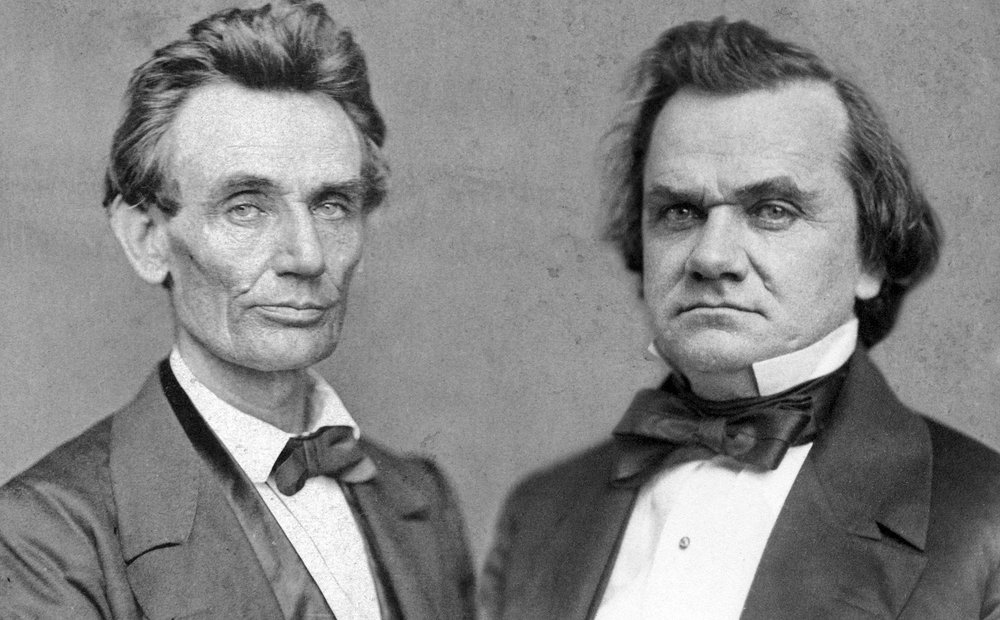

The entire episode runs for three hours and twenty-five minutes; longer than the 1858 “great debates” between Republican Abraham Lincoln and Democrat opponent Stephen Douglas. Of course, the worlds both podcast and oratory inhabited are alien to one another. Commentators chopped up Rogan’s podcast into soundbites, often decontextualised to fit identitarian, binary narratives. Setting aside three hours of screen time to focus on one debate is folly, considering the sheer amount of content on offer at any given time.

The computers are using us to profit from us; with the soil fertile for commodifying dissent, how does one cash in using the modern mass surveillance, binary-oriented media ecology?

Next Chapter: Angry Reacts Only – Harvesting Cash from the Media Ecology