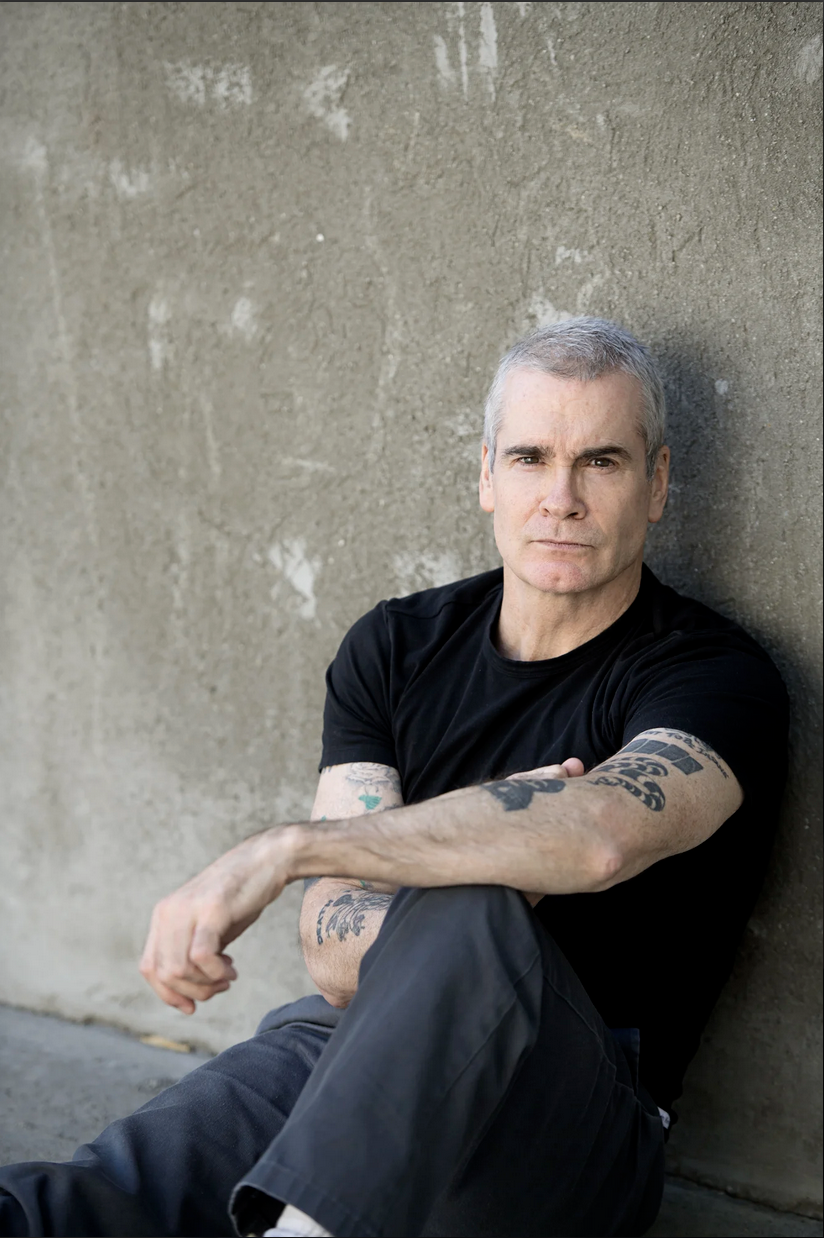

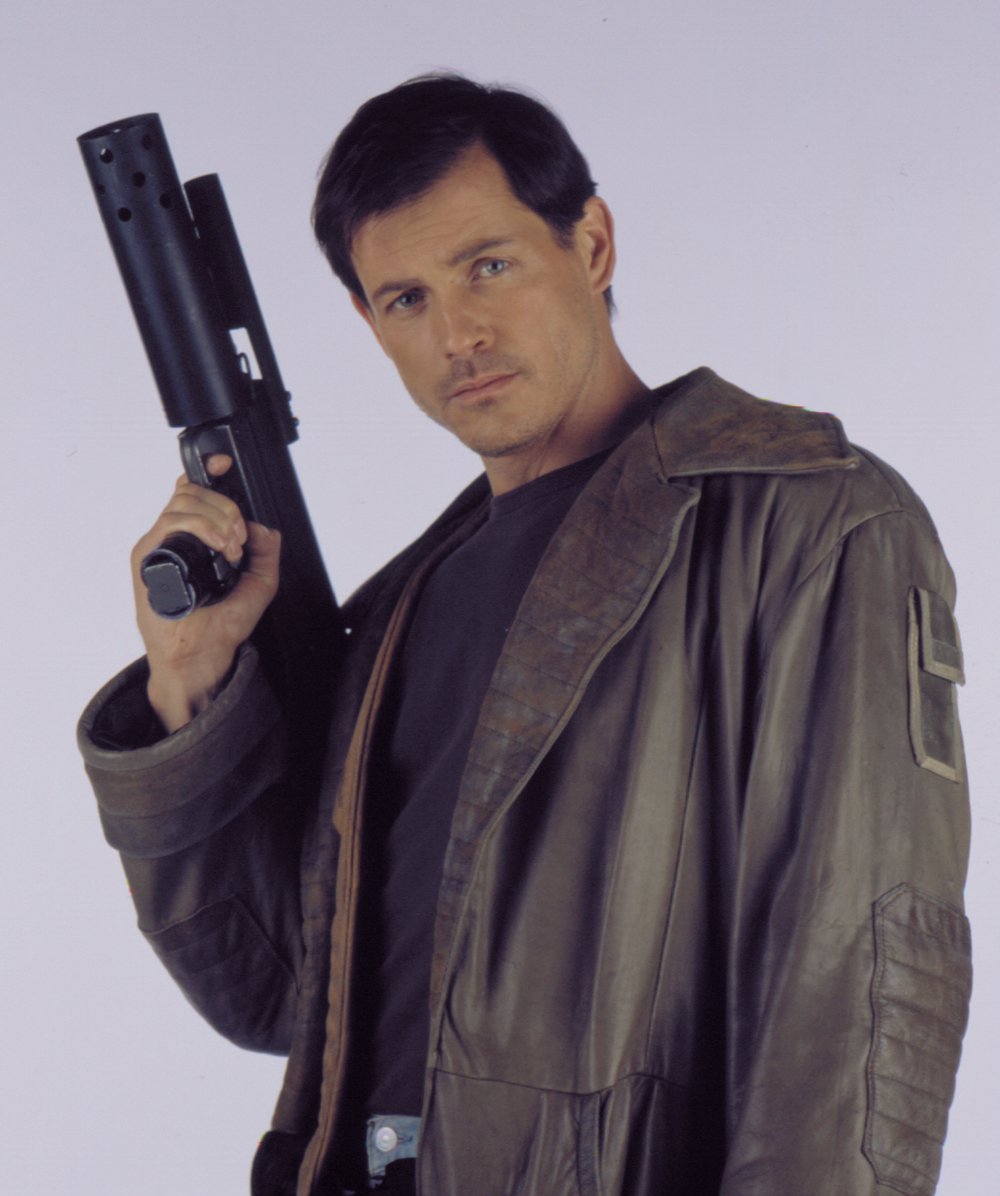

Michael Paré as Dante Montana.

Michael Paré as Dante Montana.

I owe low-budget sci-fi series Starhunter Redux, which I've been watching on Amazon Prime, an apology.

I'm sorry for calling you "total ass", that your sets look like total amateur shit, and for saying you're worse than Star Trek: Voyager on a bad day. You are none of those things.

Well, maybe a few of those things. The obscure, 44-episode series was definitely shot on a shoestring. Not a "Doctor Who in the 70s" tin-foil and cellophane budget, but pretty close. This "Redux" version released in 2017 updates the CGI shots and visuals...I can only imagine what VideoToaster monstrosity came before it.

As for the show itself, it's fairly simple as sci-fi premises go. It's the future, 2275. A rag tag motley crew of bounty hunters traipse frontier star systems hunting escaped criminals. They fly about in their retrofitted cruise liner, the "Tulip." It's crewed by a stoic, cowboy looking, anti-heroic captain (Michael Paré as Dante Montana); an impulsive yet tortured ex-soldier first mate (Claudette Roche as Lucretia Scott); and Dante's adopted niece (Tanya Allen as Percy Montana) serving as chief engineer, comic relief, and a child-like naive foil to the hard-boiled command crew. Oh, and there's a floating AI called Caravaggio (Murray Melvin), who's a cross between Batman's Alfred and the Mother on the Nostromo (Alien). I wish I was kidding.

Spoilers ahead.

Having a look through Amazon Prime, I thought I'd give it a go. I fucking loved Space Precinct 2040, another streaming hidden gem.

Oh boy. It did not start well.

The CGI was something out of a student project; sets held together with bubblegum and balsa wood. Red Dwarf could have pulled this off...but it was supposed to be funny. Then the story began.

I was laughing my ass off in the first episode; a leader of the shadowy organisation "The Orchard" kept referring to "genes" over and over. Eventually my mind shut down and I started thinking of denim jeans... it was all downhill from there.

However it revealed a crucial piece of lore: The Orchard is tasked with sequencing the last unknown parts of the human genome, unlocking humanity's elevation to a higher plane of existence; "The Divinity Cluster." There's a bit of shakiness to the stories, but its rather well executed science fiction nonetheless.

An entire back story to Lucretia as a soldier details her liberating a cruel medical experimentation facility on Callisto. The experiments, conducted by a Dr. Mengele style character, sparked a genocide of "pure" humans against cybernetic or genetic "augments"; the story was particularly heartbreaking, especially when she confronts the Mengele character head on.

All this sounds like they're ripping off Cowboy Bebop, Firefly, and Deus Ex: Mankind Divided, except these predate both by a number of years (Starhunter debuted in 2000: so two in the case of Firefly.) Even so, similarities to these and other shows definitely don't end there.

The series thus far has a Doctor Who vibe; adventurers unbound by a "hero's code" or Prime Directive. They're thrust into solving other people's problems while trying to make a quick buck. They're usually navigating some gnarly moral grey areas and duking it out in some bargain-basement action sequences.

Oh yeah, it's done on the very cheap. Which is fine - science fiction can be as cheap as it wants and still be good science fiction.

Cheap Science Fiction is Still Science Fiction

Science fiction as a visual medium requires so much of the viewer's intellectual attention and imagination to fill in the gaps. Yes friends, the Doctor's TARDIS - a blue police box - is bigger on the inside. It also goes anywhere in time and space. If it looks shoddy and made out of plastic, who cares? The fact that it exists at all requires an extreme suspension of disbelief in the first place.

The better the visuals, the more the imagination suffers. The shitty cave in Doctor Who serial The Pirate Planet, in which Tom Baker's Doctor paces back and forth because they've only got about three feet of green screen to work with, would look like complete shit if it were a crime series or adventure film (Just go to a regular cave??). The fact they're walking on a destroyed surface of a planet sandwiched between a planet crushing spaceship makes it look feel like it was plucked whole from Douglas Adams' mind and committed to film. It's real enough to tell the story; that's what matters. Those ofay with sci-fi know the score.

My beloved Babylon 5 looks like shit. Really, really bad. It'll only look worse as time goes on and production values go up. If Babylon 5 was a book reliant on imagination alone, it's would be one of the most compelling and and wonderous science fiction books ever written. It's outstanding, especially considering creator and writer J. Michael Straczynski went through an ordeal to realise his vision at all.

In modern storytelling, we can conjure near-real computer-generated, well, anything you can think of. We don't really have to imagine an "eldritch terror" like a Cthulhu or a Godzilla, it's there. We made one. See? The less imagination goes in, the less imagination we invite from the viewer. It's no wonder so many people are turned off by special effects-driven science fiction like the latest Star Wars or Marvel films.

What really killed the sci-fi imagination-factor for me was Star Trek: Discovery (in more ways than one). In one episode, hundreds of repair droids started fixing the Enterprise's phaser-scarred hull mid-battle. Commander Captain Pike ordered "damage control" - and we saw damage being controlled. In minute detail.

I would have been satisfied if he just said the line and moved on. (Hopefully as rocks fell around him and sparks flew.) Every other Star Trek incarnation had a captain or flag officer barking orders for "damage control." In our minds, the damage is being controlled. It's the 23rd/24th Century, of course it's being controlled. They have a device or a computer program called "damage control" and its function is to control damage. The end.

Please accept my apology, Starhunter Redux. I lost sight of science fiction being an intellectual, imaginitive exercise more so than a visual feast handed to me on a platter. It's the writer's job to strike the right balance between what's believable and how much we can "imagine" the story up ourselves. In this case, I think they'd nailed it. For the most part.

Some of your story elements were a bit hokey, but your ideas feel rich and engrossing. I'm only part way through, so it could fall over like the second season of Andromeda or something. I hope not.

I'll promise not to judge a TV series by the quality of its sets and CGI in future. Maybe.